Good early morning,

Into the post-Super Bowl, pre-Valentine’s Day, middle of the week-Winter Olympics mashup of February. It’s the 10th of February, and a day for me that remains as clearly etched into my memory as November 22, 1963, the 28th of January 1986, 911, or even March 4, 2020 (I actually noted in conversation earlier today once a generation there something that is culturally altering occurs.). I was a struggling student at Iowa State University, in part because I was in a major that certainly did not fit my academic strengths, and I had little to no idea how to be a dedicated student. But that evening I returned to Sioux City for the first time since Christmas break. It was a Thursday evening, and I would visit the hospital ICU, where my older brother had been a patient since falling off a ladder approximately a month before, where he was working as an electrician helping build a Burger King.

While he was still conscious albeit groggy when they got to him on the floor at the construction site that day, by the time he got to the hospital after being transported by ambulance, he suffered a massive brain hemorrhage and lapsed into a coma. He was only a couple months past his 26th birthday, and the father to three pre-school aged children and the husband to a wife who was only a quarter-century years old. Everyone in the family, except me, had been home to stand vigil in support of each other, as they watched his epic battle to live. As we were at the end of the academic quarter, and I could catch a ride back from Ames to Sioux City, I had decided to come back. When I arrived at the hospital that evening, what I saw stunned me. My brother, who was about 6 feet tall and slender, was in a somewhat fetal position in his bed, his head indented where they had removed a significant piece of his skull, and his body mass to a reduced, emaciated 89 pounds. His breathing was labored and he was unresponsive. I had never seen someone in such a dire condition, and the fact that it was my own brother was heartbreaking.

I was there at the hospital with my mother and my sister-in-law; my father was not there that evening as he decided to stay home because of a cold. As I walked into his room, I reached out and held his warm hand. His body wracked with fever, and I spoke to him softly. I stood on one side of the bed as my sister-in-law stood on the other. I remember trying to hold it together as I told him I was there. I was there to see him and I wanted him to know I loved him. We had not been there very long when he began to have a seizure. It was a significant grand mal seizure, and as his alarms went off, his nurses ushered us out of the room. We returned to the family waiting room, and I used the phone to call my father, informing him he should come to the hospital. The three of us waited silently, attempting to make small talk, but as I remember failing miserably. I do not remember how long it was before his doctor came into the room to speak with us. He talked about the gallant battle my brother was fighting to stay alive and that the complications, from the spinal meningitis to seizures, from the brain trauma and his now emaciated state, made things exponentially difficult. He had been in the room for about 10 minutes, when his nurse opened the door and came in. She looked at the doctor and simply shook her head and departed. The doctor turned and looked at the three of us and said softly, “ I’m sorry; we lost him.” I heard a whimper from my sister-in-law, and I turned and looked out the window, speaking the only word that came to mind. “Fuck!” I said to no one, as the tears began to streamed on my face. My father arrived within a half hour, but my brother was already gone. I remember my father, looking at all of us, and saying in his typically wise and stayed manner, “It is better this way.” And then his body shook as he began to cry. It was the first time I ever saw him cry. That it’s almost as overwhelming to me as the fact that my brother had just passed away.

Much of the next two days were quite a blur, and what I know now is that your body goes on autopilot merely trying to manage continued existence. Carolyn‘s father flew in from New Jersey, and on that next day, that Friday, I went to their house on South Martha Street. My grandmother, my hero, was also there, and I helped her manage the three kids while Carolyn, her father and my father made arrangements for my brother’s services and burial. It was hard to fathom the two people in their mid 20s were separated now by death rather than anything else. I remember standing on the back porch of their house that day and sobbing into my grandmother’s shoulder. I was so lost in my own life at that time that I’m not sure I processed just how tragic everything was. The same grandmother who I’ve been my hero and comforter on that day, would herself pass away, only seven months later. That year, 1977 might be the lowest point of my life – even now, almost 50 years later I am realizing how consequential those two deaths were; and I know even more clearly now how much was lost, both for me individually, and for our family collectively.

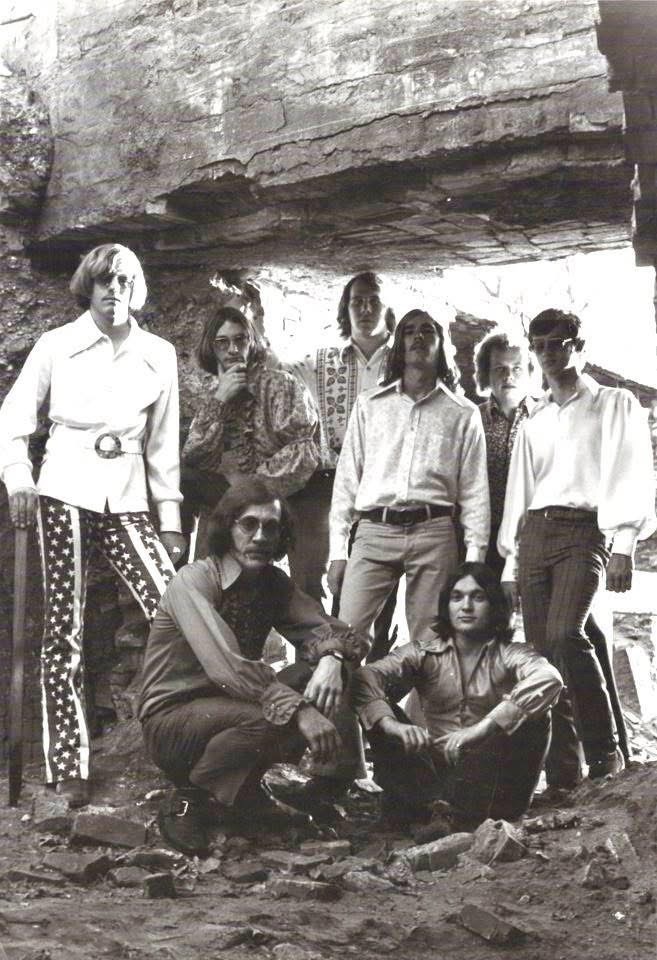

There are many things we say about death and its power over us as humans. I think the most incredible power it has and its finality in our current lives. All things we hope we might’ve said we might’ve done her now too late. For those who believe that there is something beyond, I remember the incredibly profound imagery and reality at the committal service when the body is committed back to the ground. The liturgy states (as you stand with the casket or urn before it is lowered or placed), “ This is the gate to eternal life.” What an immeasurable irony that it is in death we might find life. And yet for those left behind, life does continue, but the change is forever. The loss never disappears; certainly time can minimize the constant pain that initially seems insurmountable. And the scars from the emotional separation can reappear when least expected. For me now 50 years later, I still wonder a moments what would’ve happened had my brother lived? He was not a perfect person, as is no one, and he had many struggles. He was just profoundly human. My sister-in-law and I have talked more about him in the past year, then all the other years combined. Those conversations have been very important in helping me see and comprehend things that have been always there, but never answered. In some ways, it has healed the scar, or made it more understandable, more acceptable. Each year has February rolls around, I will revisit that night when I was the last to get home to see him. In my piety, I will always believe he waited to say goodbye. He continues to live in my memories and I know he would be amazed by his children. I hope he would be proud of how far I’ve come when I was always the younger brother who was more of a pain to him than most anything. I will always remember how talented he was and how wonderful a trombonist he was. This song will always remind me of him and the band.

Thanks for reading as always,

The Little Brother, Michael